Willowbrook, what is left

(c) Steven C. Johnsen

I found this essay so compelling that I had to publish it "as is". I had been looking for web information on Willowbrook and came up emptyhanded. It is long, I know but what Steven has to say is totally relevant and showing of how authorities take it into their hands to make decisions about other people's lives. I think it is very revealing in tandem with the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki 60 years ago, and with vry up-to-date happenings around the world ... you know what I mean.

Published with permission of

(c) Steven C. Johnsen

I found this essay so compelling that I had to publish it "as is". I had been looking for web information on Willowbrook and came up emptyhanded. It is long, I know but what Steven has to say is totally relevant and showing of how authorities take it into their hands to make decisions about other people's lives. I think it is very revealing in tandem with the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki 60 years ago, and with vry up-to-date happenings around the world ... you know what I mean.

Published with permission of

Steven Johnsen

WILLOWBROOK STATE SCHOOL

Literature Review

In 1938 the inception of an idea to house mentally disabled children on the grounds of Halloran Veterans Hospital had touched off one of the “hottest and most delicate civic battles” in Staten Island’s history (Endress 6/7/49). The furor was over Staten Islanders who were unhappy with the idea of having adult mentally ill patients living there. The long battle was concluded with a compromise that only mentally deficient children would be housed there (SIA 9/8/48). The Willowbrook State School for Mentally Deficient Children, which was scheduled to open in October 1947, was surrounded by secrecy, controversy, lack of staff, and delays right from the beginning (SIA 9/16/47).

Construction for the school began shortly before WWII and construction was delayed because of the war. A need for a local veteran’s hospital was met by temporarily using the already constructed Willowbrook buildings for Halloran Veterans Hospital. Once another suitable permanent facility in the New York area was found, the patients and personnel of the VA hospital would be moved. Many Staten Island organizations would have preferred to keep the VA hospital instead of a mental hospital (SIA 9/16/47).

In October of 1948 Dr. Frank B. Glasser, the assistant director of Willowbrook, said that the school is open in “a limited way.” At the time 48 children were being treated there. According to Dr. Glasser, only “hardship cases” had been admitted so far (Endress 10/4/48). Many people were anxious for Willowbrook to open. The State Department of Mental Hygiene had a waiting list. Two hundred and seven applications had been filed for placement of “mentally defective” children by October 1948. Hospital Commissioner Bernecker estimated that there were “at least 800 mentally defectives under 5 who should be institutionalized” (Kahn).

By late 1960 Willowbrook had grown to be the nation’s largest mental hospital holding as many as 5,700 patients. It employed over 1,700 people, which made it, by far, the largest employer on Staten Island (Endress 11/25/60). Overcrowding was a problem by 1962. Dr. Harold H. Berman, (Director of Willowbrook 1949-1964), said that steps being taken to ease over-crowding would not eliminate the problem. “If 500 or 600 of my patients were sent to another institution tomorrow, the space would be filled by others within a week” (SIA 8/23/62).

In 1965 Sen. Robert Kennedy toured Willowbrook and called it a “snake pit” (O’connor). After seeing Willowbrook Senator Kennedy said in part; “Wards built for 40 patients have 80 or more… and there are many patients living in filth and dirt, their clothing in rags, in rooms less comfortable and cheerful than the cages in which we put animals in a zoo…there are no civil liberties for those put in the cells of Willowbrook, living amidst brutality, human excrement, and intestinal disease” (Hixson).

The public disgrace of Willowbrook began in January 1972 with the firing of a doctor and a social worker who were both trying to bring the critical conditions at Willowbrook to the public’s attention. Dr. Michael Wilkins and Elizabeth Lee were not given an official reason for their termination by Dr. Jack Hammond (Director of Willowbrook 1964-1973) (Kurtin 1/7/72). They were fired “for being the prick in Hammond’s conscience and for trying to organize the patient’s parents” (Flaherty).

Director Hammond was silent and did nothing to call public attention to the horrible conditions. Staten Advance reporter Jane Kurtin and ABC Eye Witness News’s Geraldo Rivera publicly broke the story about the conditions. The terminated Dr. Wilkins aided Geraldo in his investigation (Flaherty). “When Dr. Wilkins slid back the heavy metal door of B ward, building #6, the horrible smell of the place staggered me. It was so wretched that my first thought was that the air is poisonous and it would kill me” (Rivera).

In May of 1972 Willowbrook Director Jack Hammond wrote an editorial piece in The New York Times titled: Another View of Willowbrook. In this editorial he stated. “We at Willowbrook have for years been in the forefront of the fight to improve living conditions, the staffing, and the programming of our most helpless residents.” He concluded by warning us to beware of “false prophets” and that we must “realize that there will always be people who will have no alternative but residential placement unless society chooses to return to the ancient practice of abandoning the helpless members on the mountainside” (Hammond).

A little over year after Hammond’s editorial, Bronx Congressman Mario Biaggi’s office called for a public hearing into the “mid-19th century” conditions at Willowbrook. He charged the school held patients in solitary confinement for periods up to 5 years, residents were being beat and harassed, that 75% of professional staff members are practicing illegally without licenses, patients were subjected to hepatitis experiments without consent, and tranquilizers were administered to offset staff shortages (Wittek 6/6/73). Just 2 weeks later Dr. Jack Hammond was transferred back to where he came from; Rome State School in Rome, New York (Kurtin 6/18/73).

Research Question

My research question: What happened at Willowbrook? This question may sound simple but it is very complex. I chose this topic because I wanted to know the answer to this question. I also think it is important that we remember Willowbrook. This did not go on in a far distant land, hundreds of years ago. These horrifying events occurred right where we go to school everyday, on the campus of CSI. When I tell other students that my research project is on Willowbrook I am usually asked, “What happened at Willowbrook?” In this paper I shall attempt to answer this question.

Research Design

This research project is qualitative in nature and historical. My research subject is Willowbrook State School. While the issues involved are vast and complex they occurred on 380 acres of land located at 2760 Victory Blvd. Making it micro-sociological undertaking.

I began my research at the CSI library. I asked one of the librarians at the main desk where I might find information on the former mental hospital. He looked skeptical and uneasy but he eventually led me to a room where he pointed to a book. The book was Geraldo Rivera’s Willowbrook: A Report on How it is and Why it Doesn’t Have to be That Way. I was glad to finally see a copy of it because it is, like everything else regarding Willowbrook, hard to find. A CSI professor had told me that the library had a vast amount of information about Willowbrook including newspaper clippings. I had asked the librarian about it and I was told no such information existed at CSI. I was told that if I wanted to get newspaper clippings I would have to go to the Staten Island Advance and use their microfilm.

I found this discouraging and considered changing my project. I went online for information and discovered that the CSI library has, in the Archives & Special Collections Dept., a large collection of documents, photos, and news clippings. I discovered this at an online

Staten Island Advance article that also stated; “CSI honors the memory of Willowbrook residents in ways that reflect the College’s academic mission to create and disseminate knowledge and to prepare well-trained and caring professionals”(Wu). Needless to say, I was angry that I was misled, after all, I am a CSI social work student and I hope to be a well-trained caring professional someday. Why would I be denied access or even an acknowledgement of this collection’s existence?

Armed with a copy of the article I returned to the CSI library. I decided against confronting the same librarian (perhaps he really didn’t know) and headed straight for the 2nd floor Archives and Special Collections Dept. in room 216. I told a young woman working there who I was and why I was there. I was told that there was not much to see. I simply took out my article that stated that there were thousands of documents archived there. She took the article from me, looked at it and said “Not thousands, it’s more like hundreds.” As far as I was concerned hundreds were a lot better than “not much”, which I was told a few minutes before.

I was led to a table with boxes filled with photocopies of newspaper articles that pertained exclusively to Willowbrook. The articles are dated from 1947 to 2000. I was perplexed that someone had painstakingly copied and archived over 50 years worth articles only to have the collection be kept a secret. This was a massive endeavor. Any article that had anything to do Willowbrook was included. Most of the articles were from The Staten Island Advance, although many other publications were also included.

I began sifting through the articles as the history of Willowbrook unfolded before me in the form of screaming headlines. This was a unique way of viewing history. I decided right then and there that these articles would be the basis of my research project. It seemed very fitting since it was the media that knocked over the first domino that started the chain of events that led to the eventual closing of Willowbrook. I must add that from that day on The Archives and Special Collections Dept. has been gracious, accommodating, and helpful to me.

There are many aspects to the history of Willowbrook and they are better looked at separately rather than in one long chronological sequence. The content analysis I am using is based mostly on individual case studies and reports that have been collected and reported by journalists. These reports were published back when these incidents were current events. I divided the topics into categories that I found relevant and important in the understanding of what really happened at Willowbrook.

Hepatitis Experiments on Residents: The study of hepatitis cannot be conducted in laboratories on animals because the viruses that cause infectious hepatitis seem to affect only people. The viruses were fed to 40 children between ages 5 and 10 at Willowbrook. These experiments took place between 1953 and 1958. According to Willowbrook director Dr. Harold Bermann “The consent of parents or guardians were obtained in every case.” He also said “It was done with every scientific assurance that no harm would come to the children. The children came down with the disease, of course, but their sicknesses were mild” (Smith).

Early subjects of the research were fed extracts of feces from other infected residents and later subjects were injected with a more purified strain of the virus. Parents found that they were unable to admit their child into Willowbrook unless they agreed to subject them to the hepatitis studies. Parents were given little choice but to agree to allow their children to be subjects (Stanford University).

Experts in the field began questioning the ethics of the Willowbrook experiments. In 1965, Dr. Henry K. Beecher, a professor of Research in Anesthesia at Harvard, used Willowbrook as an example of “questionable ethical studies.” In 1966 he cited Willowbrook in an article in The New England Journal of Medicine. Regarding Willowbrook’s study he wrote; “There is no right to risk an injury to one person for the benefit of others” (Medical Tribune).

In 1967 Senator Seymour Thaler, before the State Senate, charged that in the late 1950’s the hepatitis virus was injected in every child between 3 and 9 residing in Willowbrook. Dr. Jack Hammond, the new director of Willowbrook denied these allegations. He said, “There may well be 500 children who have participated in the experiments over the last 12 years but the parents of each child had given written consent.” Sen. Thaler shouted, “I don’t believe 500 parents gave their consent” (Hummel). Dr. William Bronston, a doctor in charge of hundreds at Willowbrook, referred to the hepatitis research as “patient and parent coercion.” He also stated “The issue of informed consent was invalid because the families were forced to submit if they were to get the child in.” In other words the parents would jump a long waiting list and the school would have new patients to experiment with (Dolgin).

Death of Residents: The death of Willowbrook residents was common. I can only focus on a small fraction of them.

On Friday May 14, 1965 at 4 A.M. a helpless 10-year-old patient died as a result of a scalding he received in a shower the day before. The hospital did not notify the police until 1 P.M.on Friday, 9 hours after the boy’s death. The boy was burned on over 80% of his body, and yet the burns were not discovered until 5:45 P.M. Thursday while he was being treated for a cut on his head. The cause of the head injury was not determined. The boy’s name was John K. Taylor; he was undersized and weighed only 40 pounds. He was considered a “low functioning retardate” he was able to walk but was unable to talk or feed himself. It was discovered that “little Johnny” was burned while an 18-year-old female attendant was giving him a shower. The District Attorney’s office investigation revealed, “The attendant was bathing the deceased and suddenly the plumbing gave out scalding the boy. The attendant apparently didn’t realize it at first and then attempted to conceal it from her superiors.” Neither the hospital nor the police would take any disciplinary action against her (Mallon & Moberley). After an investigation the cause of the boy’s burns was determined to be the school’s “antiquated plumbing system.” A similar death occurred the previous February in which a 42-year-old patient was also scalded in the shower (Wittek 5/18/65).

A little over a month later 12 year old Renee Meckler was strangled to death by a restraining device that was used to keep her in a chair. According to Willowbrook Director Hammond, the girl was subject to epileptic seizures and was unable to sit without being strapped into the chair (SIA 6/22/65). The director revealed that an improper safety device was used. The girl was not strapped in the proper way because an improper safety device, which is not permitted, was used. Administrative action against the two employees responsible was being considered. This death along with the two scalding victim’s deaths went before a grand jury (SIA 6/23/65). While all of these deaths were presented before grand jury investigations I found nothing mentioned of them again in this collection of newspaper articles.

I found articles pertaining to 2 more deaths at Willowbrook in the year 1965 bringing the total to 5. These are, of course, only the ones that were reported in the newspaper. I believe that the number of deaths is much higher. Class actions were brought on by the Civil Liberties Union and The Legal Aid Society. The suit charges that 2 to 3 patients die each week, often from choking on food (Oelsner). In The New York Post on January 19, 1972 columnist Pete Hamill wrote, “ From April 1, 1970 to March 31, 1971 there were 104 deaths at Willowbrook. During the eight month period from April 1, 1971 to November 31, 1971 – when the loss of staff was beginning to destroy any pretense of care – there were 97 deaths” (Hamill).

Physical Abuse of Residents: Raymond and Ethel Silvers would visit their daughter Paula every Sunday. They often found her with welts and bruises on her body. A staff member never told them or reported the incidents and Paula was too retarded to tell them herself. They would take her off campus to a diner in Brooklyn. On the way back Paula would moan. When they were driving over the Verrazano Bridge she would cry. Paula was so petrified; as they got closer to Willowbrook her cries would turn to screams (Rothman 18 – 20).

Mrs. Eleanor Janoven was going to take her son Mark, a Willowbrook resident, to a private dentist but she was told that Mark had a cold and was in the infirmary. She decided to take him anyway. When she got there the attendant took her aside and told her something was wrong and led her into the infirmary. When they pulled the sheet off Mark, Mrs. Janoven saw that her son’s back was so badly covered with welts that she couldn’t see the color of his skin. He was badly beaten (Dolgin).

Neglect of Residents: A Public Health Hospital nurse, where Willowbrook patients were sometimes taken, recounted a horrific story that happened when they were removing a patient’s cast. “The cast was rotted and broken off in several places. There was a foul odor of urine and feces. There were maggots crawling out from under it. Before the cast was removed 35 to 40 maggots were picked off. There were many maggots in the wound itself and there was a large black bug embedded in the wound” (Rothman 108).

One of the parents related an account of neglect in the form of starvation. “They fill up the bottles and throw them into a line of cribs. If the baby takes the bottle fine, if he doesn’t, he doesn’t eat. A little later the attendant rolls around a cart like in a supermarket and picks up the bottles” (Mallon).

Overcrowding and Shortage of Staff: In 1965 there was a headcount of 6,055 children and adult patients at Willowbrook. The school had a capacity was for 4,500. The overcrowding was uneven. Some wards were filled up just to capacity while others were 100% overcrowded (Wiesner 8/4/65). To add to the problem there were only 2,400 employees at the time (Wiesner 8/3/65). I must note here that the 2,400 employees consisted of ward attendants, nurses, doctors, social workers, dieticians, cooks, housekeepers, maintenance workers, security, and administrative staff. These positions were divided into 3 eight-hour shifts (Clarke).

For institutions such as Willowbrook, the National Accreditation Council for Facilities for the Mentally Retarded recommends a patient-to-attendant ratio of 4 to 1. Willowbrook was lucky if it had a ratio of 30 to 1. In just a one year period, November 30, 1970 to December 8, 1971, the resident population rose from 5,096 to 6,104 while the staff decreased from 3,628 to 2,716. Resident increase:1,008 – Staff decrease:3,052 (Sibley).

As of January 1972 (the same month Rivera began his exposÈ) Willowbrook’s budget allowed the employment of 3,505 people. By January 24,1972 only 2,838 of them were filled. The State had permanently removed 24 positions and had put a hiring freeze on 589 others (Clarke).

The Beginning of the End: On Wednesday January 5, 1972 Dr. Michael Wilkins and Elizabeth Lee, a social worker, were fired from their positions at Willowbrook because they were instrumental in bringing the horrible conditions to the public eye (Kurtin 1/7/72). The Staten Island Advance had been publishing articles about the horrendous conditions at Willowbrook. In January 1972 Geraldo Rivera aired a series of televised reports on Willowbrook (Kennedy).

A rally was held at Willowbrook on Tuesday January 11, 1972 by a group of parents demanding the reinstatement of Dr. Wilkins and Ms. Lee. They attempted to gain entrance and confront Director Hammond. Malachy McCourt, who had a stepdaughter in Willowbrook, along with the president of the Federation of Parents Organizations for the New York State Mental Institutions, Max Scneier, led the group. “Scneier and McCourt teamed up for a combined effort of kicking down the front door, while Mrs. Schneier repeatedly hit a guard on the head and shoulders with the stick of a place card she was carrying as the man blocked the entrance’ (Kurtin 1/11/72).

They pushed their way in and went into Director Jack Hammond’s office. McCourt confronted the director, he asked, “How long has it been since you laid your hands on a child to heal him instead of fiddling with your papers up here in this centrally air-conditioned building with carpets and beautiful furniture? There is no shit here. There is no piss here. There is no disease here” (Rothman 46).

The Consent Decree: The end result of The Staten Island Advance articles, Geraldo Rivera’s broadcast, and the legal action taken by the parents was the signing of a consent judgment in 1975. (Kennedy). The Consent Decree, which was signed by Governor Hugh Carey, was a civil rights law. New York State became obligated to provide housing and programs for the 6,000+ residents (Nyback). The April 30, 1975 signing of the Willowbrook Consent Decree, the state law that “triggered a flood of reforms nationwide concerning the housing and care of the mentally retarded and others with developmental disabilities.” Developmentally disabled Americans have become deinstitionalized, by the enactment of similar laws. They now live in supervised group homes that are intermingled within regular neighborhoods (Paquette).

Conclusion

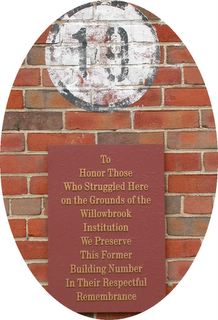

I found the subject matter of this research project difficult. It was often depressing. I look at the College of Staten Island campus in a different way now. I try to wonder what it used to be like. Instead of college students going about their daily activities, I try to picture the frail and helpless Willowbrook residents. What were they doing? What were they thinking? I look around and see no evidence of the horrors that existed here. There is one plaque, located on the back wall of building 3S. It is so small that I’ve walked passed it hundreds of times and never noticed it. It was while researching Willowbrook that I learned of its existence. Why try to hide Willowbrook’s legacy? Old faded building numbers on the sides of refurbished buildings are all that is left of what used to be.

I had to persevere in order to find the Willowbrook information in the CSI library. Rather than hiding this information, CSI should encourage students to learn about what had happened here. CSI has nothing to hide. The Consent Decree was signed and the Willowbrook residents became protected and free. There is no reason to keep this story a secret. I believe that because of secrets, the conditions at Willowbrook were able to exist for as long as they did.

WILLOWBROOK STATE SCHOOL

Literature Review

In 1938 the inception of an idea to house mentally disabled children on the grounds of Halloran Veterans Hospital had touched off one of the “hottest and most delicate civic battles” in Staten Island’s history (Endress 6/7/49). The furor was over Staten Islanders who were unhappy with the idea of having adult mentally ill patients living there. The long battle was concluded with a compromise that only mentally deficient children would be housed there (SIA 9/8/48). The Willowbrook State School for Mentally Deficient Children, which was scheduled to open in October 1947, was surrounded by secrecy, controversy, lack of staff, and delays right from the beginning (SIA 9/16/47).

Construction for the school began shortly before WWII and construction was delayed because of the war. A need for a local veteran’s hospital was met by temporarily using the already constructed Willowbrook buildings for Halloran Veterans Hospital. Once another suitable permanent facility in the New York area was found, the patients and personnel of the VA hospital would be moved. Many Staten Island organizations would have preferred to keep the VA hospital instead of a mental hospital (SIA 9/16/47).

In October of 1948 Dr. Frank B. Glasser, the assistant director of Willowbrook, said that the school is open in “a limited way.” At the time 48 children were being treated there. According to Dr. Glasser, only “hardship cases” had been admitted so far (Endress 10/4/48). Many people were anxious for Willowbrook to open. The State Department of Mental Hygiene had a waiting list. Two hundred and seven applications had been filed for placement of “mentally defective” children by October 1948. Hospital Commissioner Bernecker estimated that there were “at least 800 mentally defectives under 5 who should be institutionalized” (Kahn).

By late 1960 Willowbrook had grown to be the nation’s largest mental hospital holding as many as 5,700 patients. It employed over 1,700 people, which made it, by far, the largest employer on Staten Island (Endress 11/25/60). Overcrowding was a problem by 1962. Dr. Harold H. Berman, (Director of Willowbrook 1949-1964), said that steps being taken to ease over-crowding would not eliminate the problem. “If 500 or 600 of my patients were sent to another institution tomorrow, the space would be filled by others within a week” (SIA 8/23/62).

In 1965 Sen. Robert Kennedy toured Willowbrook and called it a “snake pit” (O’connor). After seeing Willowbrook Senator Kennedy said in part; “Wards built for 40 patients have 80 or more… and there are many patients living in filth and dirt, their clothing in rags, in rooms less comfortable and cheerful than the cages in which we put animals in a zoo…there are no civil liberties for those put in the cells of Willowbrook, living amidst brutality, human excrement, and intestinal disease” (Hixson).

The public disgrace of Willowbrook began in January 1972 with the firing of a doctor and a social worker who were both trying to bring the critical conditions at Willowbrook to the public’s attention. Dr. Michael Wilkins and Elizabeth Lee were not given an official reason for their termination by Dr. Jack Hammond (Director of Willowbrook 1964-1973) (Kurtin 1/7/72). They were fired “for being the prick in Hammond’s conscience and for trying to organize the patient’s parents” (Flaherty).

Director Hammond was silent and did nothing to call public attention to the horrible conditions. Staten Advance reporter Jane Kurtin and ABC Eye Witness News’s Geraldo Rivera publicly broke the story about the conditions. The terminated Dr. Wilkins aided Geraldo in his investigation (Flaherty). “When Dr. Wilkins slid back the heavy metal door of B ward, building #6, the horrible smell of the place staggered me. It was so wretched that my first thought was that the air is poisonous and it would kill me” (Rivera).

In May of 1972 Willowbrook Director Jack Hammond wrote an editorial piece in The New York Times titled: Another View of Willowbrook. In this editorial he stated. “We at Willowbrook have for years been in the forefront of the fight to improve living conditions, the staffing, and the programming of our most helpless residents.” He concluded by warning us to beware of “false prophets” and that we must “realize that there will always be people who will have no alternative but residential placement unless society chooses to return to the ancient practice of abandoning the helpless members on the mountainside” (Hammond).

A little over year after Hammond’s editorial, Bronx Congressman Mario Biaggi’s office called for a public hearing into the “mid-19th century” conditions at Willowbrook. He charged the school held patients in solitary confinement for periods up to 5 years, residents were being beat and harassed, that 75% of professional staff members are practicing illegally without licenses, patients were subjected to hepatitis experiments without consent, and tranquilizers were administered to offset staff shortages (Wittek 6/6/73). Just 2 weeks later Dr. Jack Hammond was transferred back to where he came from; Rome State School in Rome, New York (Kurtin 6/18/73).

Research Question

My research question: What happened at Willowbrook? This question may sound simple but it is very complex. I chose this topic because I wanted to know the answer to this question. I also think it is important that we remember Willowbrook. This did not go on in a far distant land, hundreds of years ago. These horrifying events occurred right where we go to school everyday, on the campus of CSI. When I tell other students that my research project is on Willowbrook I am usually asked, “What happened at Willowbrook?” In this paper I shall attempt to answer this question.

Research Design

This research project is qualitative in nature and historical. My research subject is Willowbrook State School. While the issues involved are vast and complex they occurred on 380 acres of land located at 2760 Victory Blvd. Making it micro-sociological undertaking.

I began my research at the CSI library. I asked one of the librarians at the main desk where I might find information on the former mental hospital. He looked skeptical and uneasy but he eventually led me to a room where he pointed to a book. The book was Geraldo Rivera’s Willowbrook: A Report on How it is and Why it Doesn’t Have to be That Way. I was glad to finally see a copy of it because it is, like everything else regarding Willowbrook, hard to find. A CSI professor had told me that the library had a vast amount of information about Willowbrook including newspaper clippings. I had asked the librarian about it and I was told no such information existed at CSI. I was told that if I wanted to get newspaper clippings I would have to go to the Staten Island Advance and use their microfilm.

I found this discouraging and considered changing my project. I went online for information and discovered that the CSI library has, in the Archives & Special Collections Dept., a large collection of documents, photos, and news clippings. I discovered this at an online

Staten Island Advance article that also stated; “CSI honors the memory of Willowbrook residents in ways that reflect the College’s academic mission to create and disseminate knowledge and to prepare well-trained and caring professionals”(Wu). Needless to say, I was angry that I was misled, after all, I am a CSI social work student and I hope to be a well-trained caring professional someday. Why would I be denied access or even an acknowledgement of this collection’s existence?

Armed with a copy of the article I returned to the CSI library. I decided against confronting the same librarian (perhaps he really didn’t know) and headed straight for the 2nd floor Archives and Special Collections Dept. in room 216. I told a young woman working there who I was and why I was there. I was told that there was not much to see. I simply took out my article that stated that there were thousands of documents archived there. She took the article from me, looked at it and said “Not thousands, it’s more like hundreds.” As far as I was concerned hundreds were a lot better than “not much”, which I was told a few minutes before.

I was led to a table with boxes filled with photocopies of newspaper articles that pertained exclusively to Willowbrook. The articles are dated from 1947 to 2000. I was perplexed that someone had painstakingly copied and archived over 50 years worth articles only to have the collection be kept a secret. This was a massive endeavor. Any article that had anything to do Willowbrook was included. Most of the articles were from The Staten Island Advance, although many other publications were also included.

I began sifting through the articles as the history of Willowbrook unfolded before me in the form of screaming headlines. This was a unique way of viewing history. I decided right then and there that these articles would be the basis of my research project. It seemed very fitting since it was the media that knocked over the first domino that started the chain of events that led to the eventual closing of Willowbrook. I must add that from that day on The Archives and Special Collections Dept. has been gracious, accommodating, and helpful to me.

There are many aspects to the history of Willowbrook and they are better looked at separately rather than in one long chronological sequence. The content analysis I am using is based mostly on individual case studies and reports that have been collected and reported by journalists. These reports were published back when these incidents were current events. I divided the topics into categories that I found relevant and important in the understanding of what really happened at Willowbrook.

Hepatitis Experiments on Residents: The study of hepatitis cannot be conducted in laboratories on animals because the viruses that cause infectious hepatitis seem to affect only people. The viruses were fed to 40 children between ages 5 and 10 at Willowbrook. These experiments took place between 1953 and 1958. According to Willowbrook director Dr. Harold Bermann “The consent of parents or guardians were obtained in every case.” He also said “It was done with every scientific assurance that no harm would come to the children. The children came down with the disease, of course, but their sicknesses were mild” (Smith).

Early subjects of the research were fed extracts of feces from other infected residents and later subjects were injected with a more purified strain of the virus. Parents found that they were unable to admit their child into Willowbrook unless they agreed to subject them to the hepatitis studies. Parents were given little choice but to agree to allow their children to be subjects (Stanford University).

Experts in the field began questioning the ethics of the Willowbrook experiments. In 1965, Dr. Henry K. Beecher, a professor of Research in Anesthesia at Harvard, used Willowbrook as an example of “questionable ethical studies.” In 1966 he cited Willowbrook in an article in The New England Journal of Medicine. Regarding Willowbrook’s study he wrote; “There is no right to risk an injury to one person for the benefit of others” (Medical Tribune).

In 1967 Senator Seymour Thaler, before the State Senate, charged that in the late 1950’s the hepatitis virus was injected in every child between 3 and 9 residing in Willowbrook. Dr. Jack Hammond, the new director of Willowbrook denied these allegations. He said, “There may well be 500 children who have participated in the experiments over the last 12 years but the parents of each child had given written consent.” Sen. Thaler shouted, “I don’t believe 500 parents gave their consent” (Hummel). Dr. William Bronston, a doctor in charge of hundreds at Willowbrook, referred to the hepatitis research as “patient and parent coercion.” He also stated “The issue of informed consent was invalid because the families were forced to submit if they were to get the child in.” In other words the parents would jump a long waiting list and the school would have new patients to experiment with (Dolgin).

Death of Residents: The death of Willowbrook residents was common. I can only focus on a small fraction of them.

On Friday May 14, 1965 at 4 A.M. a helpless 10-year-old patient died as a result of a scalding he received in a shower the day before. The hospital did not notify the police until 1 P.M.on Friday, 9 hours after the boy’s death. The boy was burned on over 80% of his body, and yet the burns were not discovered until 5:45 P.M. Thursday while he was being treated for a cut on his head. The cause of the head injury was not determined. The boy’s name was John K. Taylor; he was undersized and weighed only 40 pounds. He was considered a “low functioning retardate” he was able to walk but was unable to talk or feed himself. It was discovered that “little Johnny” was burned while an 18-year-old female attendant was giving him a shower. The District Attorney’s office investigation revealed, “The attendant was bathing the deceased and suddenly the plumbing gave out scalding the boy. The attendant apparently didn’t realize it at first and then attempted to conceal it from her superiors.” Neither the hospital nor the police would take any disciplinary action against her (Mallon & Moberley). After an investigation the cause of the boy’s burns was determined to be the school’s “antiquated plumbing system.” A similar death occurred the previous February in which a 42-year-old patient was also scalded in the shower (Wittek 5/18/65).

A little over a month later 12 year old Renee Meckler was strangled to death by a restraining device that was used to keep her in a chair. According to Willowbrook Director Hammond, the girl was subject to epileptic seizures and was unable to sit without being strapped into the chair (SIA 6/22/65). The director revealed that an improper safety device was used. The girl was not strapped in the proper way because an improper safety device, which is not permitted, was used. Administrative action against the two employees responsible was being considered. This death along with the two scalding victim’s deaths went before a grand jury (SIA 6/23/65). While all of these deaths were presented before grand jury investigations I found nothing mentioned of them again in this collection of newspaper articles.

I found articles pertaining to 2 more deaths at Willowbrook in the year 1965 bringing the total to 5. These are, of course, only the ones that were reported in the newspaper. I believe that the number of deaths is much higher. Class actions were brought on by the Civil Liberties Union and The Legal Aid Society. The suit charges that 2 to 3 patients die each week, often from choking on food (Oelsner). In The New York Post on January 19, 1972 columnist Pete Hamill wrote, “ From April 1, 1970 to March 31, 1971 there were 104 deaths at Willowbrook. During the eight month period from April 1, 1971 to November 31, 1971 – when the loss of staff was beginning to destroy any pretense of care – there were 97 deaths” (Hamill).

Physical Abuse of Residents: Raymond and Ethel Silvers would visit their daughter Paula every Sunday. They often found her with welts and bruises on her body. A staff member never told them or reported the incidents and Paula was too retarded to tell them herself. They would take her off campus to a diner in Brooklyn. On the way back Paula would moan. When they were driving over the Verrazano Bridge she would cry. Paula was so petrified; as they got closer to Willowbrook her cries would turn to screams (Rothman 18 – 20).

Mrs. Eleanor Janoven was going to take her son Mark, a Willowbrook resident, to a private dentist but she was told that Mark had a cold and was in the infirmary. She decided to take him anyway. When she got there the attendant took her aside and told her something was wrong and led her into the infirmary. When they pulled the sheet off Mark, Mrs. Janoven saw that her son’s back was so badly covered with welts that she couldn’t see the color of his skin. He was badly beaten (Dolgin).

Neglect of Residents: A Public Health Hospital nurse, where Willowbrook patients were sometimes taken, recounted a horrific story that happened when they were removing a patient’s cast. “The cast was rotted and broken off in several places. There was a foul odor of urine and feces. There were maggots crawling out from under it. Before the cast was removed 35 to 40 maggots were picked off. There were many maggots in the wound itself and there was a large black bug embedded in the wound” (Rothman 108).

One of the parents related an account of neglect in the form of starvation. “They fill up the bottles and throw them into a line of cribs. If the baby takes the bottle fine, if he doesn’t, he doesn’t eat. A little later the attendant rolls around a cart like in a supermarket and picks up the bottles” (Mallon).

Overcrowding and Shortage of Staff: In 1965 there was a headcount of 6,055 children and adult patients at Willowbrook. The school had a capacity was for 4,500. The overcrowding was uneven. Some wards were filled up just to capacity while others were 100% overcrowded (Wiesner 8/4/65). To add to the problem there were only 2,400 employees at the time (Wiesner 8/3/65). I must note here that the 2,400 employees consisted of ward attendants, nurses, doctors, social workers, dieticians, cooks, housekeepers, maintenance workers, security, and administrative staff. These positions were divided into 3 eight-hour shifts (Clarke).

For institutions such as Willowbrook, the National Accreditation Council for Facilities for the Mentally Retarded recommends a patient-to-attendant ratio of 4 to 1. Willowbrook was lucky if it had a ratio of 30 to 1. In just a one year period, November 30, 1970 to December 8, 1971, the resident population rose from 5,096 to 6,104 while the staff decreased from 3,628 to 2,716. Resident increase:1,008 – Staff decrease:3,052 (Sibley).

As of January 1972 (the same month Rivera began his exposÈ) Willowbrook’s budget allowed the employment of 3,505 people. By January 24,1972 only 2,838 of them were filled. The State had permanently removed 24 positions and had put a hiring freeze on 589 others (Clarke).

The Beginning of the End: On Wednesday January 5, 1972 Dr. Michael Wilkins and Elizabeth Lee, a social worker, were fired from their positions at Willowbrook because they were instrumental in bringing the horrible conditions to the public eye (Kurtin 1/7/72). The Staten Island Advance had been publishing articles about the horrendous conditions at Willowbrook. In January 1972 Geraldo Rivera aired a series of televised reports on Willowbrook (Kennedy).

A rally was held at Willowbrook on Tuesday January 11, 1972 by a group of parents demanding the reinstatement of Dr. Wilkins and Ms. Lee. They attempted to gain entrance and confront Director Hammond. Malachy McCourt, who had a stepdaughter in Willowbrook, along with the president of the Federation of Parents Organizations for the New York State Mental Institutions, Max Scneier, led the group. “Scneier and McCourt teamed up for a combined effort of kicking down the front door, while Mrs. Schneier repeatedly hit a guard on the head and shoulders with the stick of a place card she was carrying as the man blocked the entrance’ (Kurtin 1/11/72).

They pushed their way in and went into Director Jack Hammond’s office. McCourt confronted the director, he asked, “How long has it been since you laid your hands on a child to heal him instead of fiddling with your papers up here in this centrally air-conditioned building with carpets and beautiful furniture? There is no shit here. There is no piss here. There is no disease here” (Rothman 46).

The Consent Decree: The end result of The Staten Island Advance articles, Geraldo Rivera’s broadcast, and the legal action taken by the parents was the signing of a consent judgment in 1975. (Kennedy). The Consent Decree, which was signed by Governor Hugh Carey, was a civil rights law. New York State became obligated to provide housing and programs for the 6,000+ residents (Nyback). The April 30, 1975 signing of the Willowbrook Consent Decree, the state law that “triggered a flood of reforms nationwide concerning the housing and care of the mentally retarded and others with developmental disabilities.” Developmentally disabled Americans have become deinstitionalized, by the enactment of similar laws. They now live in supervised group homes that are intermingled within regular neighborhoods (Paquette).

Conclusion

I found the subject matter of this research project difficult. It was often depressing. I look at the College of Staten Island campus in a different way now. I try to wonder what it used to be like. Instead of college students going about their daily activities, I try to picture the frail and helpless Willowbrook residents. What were they doing? What were they thinking? I look around and see no evidence of the horrors that existed here. There is one plaque, located on the back wall of building 3S. It is so small that I’ve walked passed it hundreds of times and never noticed it. It was while researching Willowbrook that I learned of its existence. Why try to hide Willowbrook’s legacy? Old faded building numbers on the sides of refurbished buildings are all that is left of what used to be.

I had to persevere in order to find the Willowbrook information in the CSI library. Rather than hiding this information, CSI should encourage students to learn about what had happened here. CSI has nothing to hide. The Consent Decree was signed and the Willowbrook residents became protected and free. There is no reason to keep this story a secret. I believe that because of secrets, the conditions at Willowbrook were able to exist for as long as they did.

5 Comments:

Thank you for posting this article. I too have tried to research the internet for specifics on Willowbrook and couldn't really find any. I am planning on getting Rivera's book - if I can find it. Thanks again.

Bonnie

Thanks for the comment,Bonnie. It´s nice to get feedback.

i have researched many a willowbrook file, and what you have wrote is a wonderful piece. i formerly worked with patients who resided there. i am a nurse in upstate n.y and i cannot use the example of willowbrook enough times to my staff as an example of quality of care...beautiful work my good man. and good lock in your work in the future.

Angel, what a fitting name for a Nurse. I was proud to post this essay by Steven J, a student at College of Staten Island campused at what was formerly Willowbrook Institution. It is long, I know but I couldn't see fit to chop off anything.

There is another side to this story. My Mother was the President of the Benevolent Society for Retarded Children, willow brook State School (as it was know then). She and Jack Hammond talked every night for hours (I know because I had very little time with my Mother growing up - my Brother died at Willowbrook State School and my Mother delved into making conditions better). Geraldo's expose was focused on one thing only - making Geraldo famous - not the truth. So what is the truth - Jack Hammond hated the conditions at Willowbrook but like all civil servants had a budget he had to operate under. I remember my Mother getting off the phone crying when Jack told her of the scoldings. After dinner Jack would walk the facility and make surprise visits into wards. Within minutes of his first visit every ward would know he was walking around. Jack asked my Mother to have the parent group install "governors" on the water heaters to keep the showers from scolding the kids. I remember one time Jack said to my Mother that a group of kids had been admitted who he believed were not retarded but hard of hearing or deaf. He asked her again to get the parent group to bring in a doctor to conduct hearing tests. Again the parent group did that and the kids were released. There were phone conversations every night asking for help. Yes conditions were horrible but it all came down to money and resources all of which Jack had no control over. He was the fall guy for a system that did not care about these kids. Be as critical as you want but remember times have changed. In the 50's and before people were embarrassed to admit they had a retarded child. There was little to no support systems to help them. We had not advanced in our "special needs" programs as we have today. The world was a different place. Geraldo Rivera told one side of the story. He never bothered to try to understand the other. Jack was a Naval officer and believed strongly in its principles including the Chain of Command. He would never turn on his superiors but behind the scenes he was begging for help daily. Again - one last time - when judging - judge with a 50's mentality.

Post a Comment

<< Home